We’re thrilled to announce that our former employee, Emily Harris, is featured in an article on The Huffington Post. Please see the article below!

Artist Emily Harris Investigates How a Body Imprints Itself on an Environment

Written by Jacqueline Bishop (Author, Artist, NYU Professor)

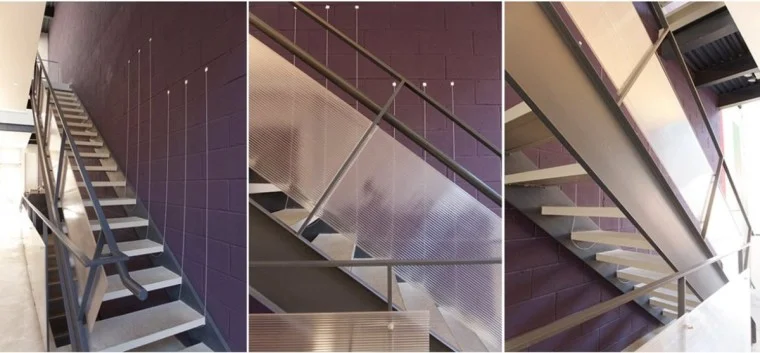

At first they were a nuisance: the long, thin pieces of thread that Emily Harris installed in a hallway as part of her thesis show. For the first few days I would continually walk into and become tangled up in the threads, and, truth be told, I felt that the threads were getting in my way. As the summer progressed, however, I got used to the presence of the threads in the hallway, and then there was a subtle shift, in that I could actually see the threads as they swayed or were still in the long, narrow hallway. Before long I started walking around the threads. And wouldn’t you know it, at the conclusion of Harris’s thesis show, when she took them down, I actually missed the long, slender, at first invisible, pieces of threads. And in this way Emily Harris had succeeded in not only making the invisible visible, but in doing what she had set out to do in her thesis work: show us how we as humans are activated by the environment around us.

Emily Harris was born in St. Paul, Minnesota and grew up on a large, rambling farm that would leave an indelible imprint upon her. “We lived in an old farmhouse that had woods in the back, wild turkeys about the yard, and a large garden. My sister and I had a lot of time to explore the woods and nature, and I guess this continues to show up in my work because I remain very interested in the collaboration between people and the environment,” Harris told me.

During high school she got very interested in photography and, through a chance encounter, took a photograph of three ducks on a river that heightened her appreciation even more of the environment. At Kenyon College as an art and philosophy major, her art practice would expand to include drawing, video and installation work. Her thesis show at Kenyon College was a video piece in which she investigated where in the body memories and images are kept. The work consisted of projections, video and audio pieces, and transparencies.

After graduating from Kenyon College, Harris worked at an aerial mapping company which furthered her appreciation for how the land was changing and transforming, due in large part to changing infrastructure and technology. “It was an interesting time for me doing this work, because technologies were rapidly changing and I felt as if I was straddling the analog and digital worlds.”

This straddling of worlds would help her enormously in the work that she was later to do.

Wanting a change from the life she had always known, and seeking more of an artistic community, in 2005 Emily Harris moved to New York City and started working at A.I.R Gallery — a female-run gallery that has been advocating for women in the arts since 1972. At A.I.R she not only met fantastic artists but her time at the gallery expanded her idea of what art could be. “Growing up in the Midwest and just coming out of undergrad, I confess that I had a pretty limited idea of what art could be,” she admitted. “At A.I.R I learned that art did not have to be something that was saleable. That realization alone changed so many things for me. What I saw and absorbed at A.I.R was that artists could get together through consensus and democratically run an organization. I also slowly started to get the idea out of my head that drawing had to look a certain way and had to be ‘elegant.’ All of that was exploded and I grew to love the work of artists that helped me challenge my own notions of what art could or should be.”

Harris would work at the gallery for five years, before branching out to work independently with artists whose work she admired. During that time she would take trips back to Minnesota, where she had more space to make the nature-based works that she was making. Among the works she made during this period was a series of quilt patterns painted onto plywood and mounted outside the three barns on her parents’ property. She also made papier-mâché structures, architectural pieces, and trails and maps. “These works were a way for me to go back home and make things that related directly to the space, and what I learned was that ideas of home and space are intricately linked for me.”

At about this time Harris decided to go back to graduate school, but for a long while she was unclear what to study. You see, in addition to being a visual artist, Harris is also a musician and had performed a lot by then. Oftentimes she would, in both her work as a visual artist and as a musician, fuse her installation practice and her performance-based work. In time she came to see what she was doing as a musician as another form of visual art work. Increasingly, she started to give central importance to her installation and visual art work because of its relationship to the body.

“In looking back, I guess I wanted more spaces of freedom. I was resenting the restrictions and constraints of what I call “totalitarian environments” and how I had to fit my body into a given space. The visual arts seemed the place I could best work out my ideas, and so I made a decision to commit to the visual arts in the form of a graduate program. I was interested in learning more about theory and being with people who felt that art was important. In addition, at that time I was just beginning to have an inclination that my body and my installation work were ‘drawings’, but this time I was drawing in space. I started looking for a program where I could work out and understand these ideas better.”

The program she eventually settled on was Maryland Institute College of Art’s low-residency MFAST Program. She liked the fact that this program was longer than most other MFA programs, taking place over four summers, with winter sessions in between, because she did not want to go to a program that she could hurry through very quickly. Interestingly enough, despite the length of the program, Harris remembers her first few semesters at MICA as being very anxious ones. “My first summer or two there, I produced a lot of work before I started realizing that making all that work all at once was not that beneficial to me. As I slowed down I started to hone in more on what I really wanted to examine, which was the relationship of a site to a body and how the body responds to the shape and organization of a site. In slowing down I came to realize that what I was really interested in was the mutual defining of body and site.”

Consequently, in her thesis show she used threads, strings, tape and clay to call attention to her investigations. As individuals moved through the installation of threads in a long hallway, the threads would move in relationship to the currents generated, and individuals would, hopefully, as it was in my case, come to realize how something so seemingly minuscule as a piece of thread made us more aware of our environment and our bodies and how we were affecting — and in turn were affected by — the environment. It was a delicate but thoroughly effective piece of work.

“Right now, this is very important to me because there is something going on where the body is being erased,” Harris explained. “Technology in our lives is so ever-present that I feel the need to reinsert the body that, to me, is being diminished by technology. We are losing body awareness. The mutual defining of body and environment is important because there are seemingly invisible things that are affecting us that we don’t pay enough attention to.

“The body can impart really meaningful information, like we see take place in REM sleep. But I wonder how much we pay attention to and trust our own experiences and our own bodies anymore? We turn to technology too often to understand what we are feeling, what we are thinking, what we are seeing. What I hope my work will force us to do is pay more attention to our bodies and at the same time pay more attention to our environment. I would like to see us pay more attention to what they both have to say, especially to each other.”

Until next time.